My mother wrote this article for the community blog where she lives. I was very moved by it and it's the kind of thing I want to hold on to in my journal here for posterity. I no longer take my family history for granted, having lost my dad and his memories. I have been trying to devise ways to hold on to our stories, we Thompsons and Blackburns and Moons... This is a start.

The election is over, and I have been reflecting on its meaning. All of the pundits have been referring to this election as "historic." This is certainly true in two main ways--an African-American presidential nominee and the Republican nomination of a woman for vice-president. I would like to look at this election in a more personal way.

I was born in 1938 and grew up in Ft. Worth, Texas, a completely segregated city. Everything was divided into black and white: the schools, the swimming pools, the parks, the bus and train stations, the cemeteries, the movie theaters, the hospitals, the churches, the doctor's offices, the funeral homes, the neighborhoods, and the restaurants, diners, and coffee shops.

When my mother and I went downtown to shop (there were no malls back then), there were two water fountains by the elevators. One was labeled "Colored" and one "White."

I always wondered what would happen if I drank out of the wrong one. Being a child, I imagined that an alarm would sound and I would be arrested or something. So, of course, I never tried it or even asked. In public places, there had to be four restrooms divided by race and gender. (You can figure it out.) In smaller businesses, there were usually no restrooms for blacks at all. There was a very popular barbecue restaurant in what was called "Colored Town" called The Big Apple. Many whites ate there, but blacks were not allowed inside. They could go to a window in the back of the restaurant and order food to go. It may have been the original "Take Out" in Ft. Worth. I was never in a classroom with an African-American student until I started teaching in San Antonio in 1962. (San Antonio was integrated early and never had the racial conflicts that other southern cities had.)

This was the norm, and I accepted it. When I was in the 8th grade my parents and I moved, and I rode a city bus across town to and from school each day. The white people sat in the seats from the back door to the front. The black people had to sit from the back door to the rear. Of course, there are fewer seats back there. There was no sign or marker indicating this fact. Everyone just knew. Sometimes the seats at the back of the bus would all be taken, and black people had to stand crammed in the aisle in their section. The front of the bus might have plenty of empty seats, but no black people sat there, ever.

In 1968, I was teaching American History to 10th graders, and we were studying the Civil Rights Movement. I was telling the class about all these things I have written about here. The students seemed very involved in my lecture. When I got to the part about the buses, one young man raised his hand and said, "Mrs. Thompson, what did you do about it?"

There was a long silence on my part. I finally said, "Nothing." I went on to explain how I was just 13 years old and didn't think I could do anything about it even though it seemed unfair. That seemed like a lame excuse at the time and still does today.

Patsy

I was born in 1938 and grew up in Ft. Worth, Texas, a completely segregated city. Everything was divided into black and white: the schools, the swimming pools, the parks, the bus and train stations, the cemeteries, the movie theaters, the hospitals, the churches, the doctor's offices, the funeral homes, the neighborhoods, and the restaurants, diners, and coffee shops.

When my mother and I went downtown to shop (there were no malls back then), there were two water fountains by the elevators. One was labeled "Colored" and one "White."

I always wondered what would happen if I drank out of the wrong one. Being a child, I imagined that an alarm would sound and I would be arrested or something. So, of course, I never tried it or even asked. In public places, there had to be four restrooms divided by race and gender. (You can figure it out.) In smaller businesses, there were usually no restrooms for blacks at all. There was a very popular barbecue restaurant in what was called "Colored Town" called The Big Apple. Many whites ate there, but blacks were not allowed inside. They could go to a window in the back of the restaurant and order food to go. It may have been the original "Take Out" in Ft. Worth. I was never in a classroom with an African-American student until I started teaching in San Antonio in 1962. (San Antonio was integrated early and never had the racial conflicts that other southern cities had.)

This was the norm, and I accepted it. When I was in the 8th grade my parents and I moved, and I rode a city bus across town to and from school each day. The white people sat in the seats from the back door to the front. The black people had to sit from the back door to the rear. Of course, there are fewer seats back there. There was no sign or marker indicating this fact. Everyone just knew. Sometimes the seats at the back of the bus would all be taken, and black people had to stand crammed in the aisle in their section. The front of the bus might have plenty of empty seats, but no black people sat there, ever.

In 1968, I was teaching American History to 10th graders, and we were studying the Civil Rights Movement. I was telling the class about all these things I have written about here. The students seemed very involved in my lecture. When I got to the part about the buses, one young man raised his hand and said, "Mrs. Thompson, what did you do about it?"

There was a long silence on my part. I finally said, "Nothing." I went on to explain how I was just 13 years old and didn't think I could do anything about it even though it seemed unfair. That seemed like a lame excuse at the time and still does today.

Patsy

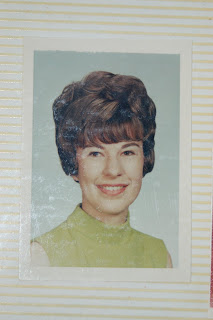

This is my mother in 1962:

And just a little later - 1969

No comments:

Post a Comment